Introduction

What if the walls, windows, roof and façades of our buildings could generate electricity, not as a mere add-on, but as an integral part of the building itself? That is the promise of Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV). Rather than mounting panels on top of a roof or beside a building, BIPV systems replace conventional building materials, embedding photovoltaic (PV) modules into roofs, façades, glazing, skylights, or shading elements. According to the working definition from IEA PVPS Task 15, BIPV refers to PV modules that function as both “building products” and “power-generating devices.” Thus, BIPV aims to merge architecture, construction, and energy generation.

In this article, we examine whether BIPV is a viable reality today – looking at definitions, applications, performance trade-offs, design workflow, economics, standards, and challenges. The goal is to give both beginners and experts a balanced, source-grounded picture of what BIPV can – and cannot – deliver.

BIPV vs Conventional PV / BAPV

According to IEA PVPS Task 15, a defining characteristic of Building-Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPV) is that the photovoltaic module must function as both a building product and a power-generating device. In other words, a BIPV module must meet all the functional requirements of a building envelope element-such as structural integrity, fire safety, weather resistance, and durability-while simultaneously producing electricity.

By contrast, a PV system that is simply mounted onto a finished building (for example, rack-mounted panels installed on an existing roof) does not replace or contribute to the building envelope. Such systems are classified as Building-Applied PV (BAPV) rather than BIPV.

Figure 1: BIPV wall at Seoul Energy Centre, Seoul. Photo: GSES

Figure 2: Solar Rooftop panels installed at a school in Maldives (BAPV). Photo: GSES

Figure 3: Difference between BAPV (left) and BIPV (right)

Because of this distinction, the smallest functional element in a BIPV system is often referred to as a “BIPV product”: a module that, if removed, would leave the building envelope incomplete and therefore must be replaced with another certified building component.

Choosing BIPV therefore means selecting a building material, not merely adding a solar device. The product must comply with all relevant building-envelope requirements: fire performance, load-bearing capacity, weather tightness, and long-term durability, as well as standard PV electrical and safety requirements. For example, IEC 63092 (“Photovoltaics in buildings – Building-integrated photovoltaic modules and systems”) specifies the technical and safety requirements that BIPV modules and systems must satisfy when used as construction products.

In recent years, regulatory and certification frameworks have evolved to acknowledge this dual identity of BIPV as both construction material and energy system. Consequently, any BIPV installation must meet both building-code requirements and photovoltaic standards, adding complexity to the design and approval process but ensuring safety, performance, and long-term reliability.

Typical BIPV Applications & Typologies

BIPV is not one-size-fits-all. Depending on building type, climate, aesthetic goals, and solar opportunity, different typologies are possible. Major application categories include:

1. Roof-integrated BIPV

Roof-integrated BIPV replaces traditional roofing materials by in roof modules, tiles, shingles, skylights or metal sheets with PV-enabled versions. This is familiar in residential pitched roofs but can also be used in flat roofs via integrated skylights or PV-roof panels. As roof components, these modules must support structural loads, ensure waterproofing, integrate with drainage/flashings, and meet fire and wind resistance standards – just like any conventional roof.

Figure 4: BIPV roof of staff canteen at Elcomponics Noida. Source: Elcomponics

2. Façade Integration and Cladding

Vertical surfaces such as external walls are often under-utilised for solar energy. BIPV enables façades to become electricity-generating surfaces by using PV modules as cladding panels, curtain-wall spandrels or ventilated façades. This is especially useful in high-rise or dense urban buildings where roof area is limited. Although vertical orientation reduces solar yield compared to optimally angled roofs, the large available surface area and often favourable east/west exposures can still make façade BIPV viable.

Figure 5: BIPV wall fencing (Seoul Energy Centre)

Photo: GSES

Figure 6: BIPV used as a sound barrier fencing wall (Seoul Energy Centre)

Photo: GSES

3. Glazed BIPV

Semi-transparent or patterned PV modules embedded in glass allow integration into windows, skylights, and atrium glazing. This enables power generation without completely sacrificing daylighting – and often adds shading / solar-control benefits. However, using BIPV glazing introduces optical and thermal trade-offs: visible transmittance, shading, solar heat gain, daylighting, and thermal performance must all be carefully balanced.

Figure 7: BIPV Semitransparent door frame. Photo: GSES

4. External Shading and Architectural Elements

Architectural elements such as canopies, awnings, louvers, pergolas, car-ports, balcony balustrades, or shading devices can host BIPV modules. In such uses, BIPV serves multifunctional purposes: structural/shading/weather-protection + power generation. Such integrated devices are particularly attractive for commercial or institutional buildings where aesthetics, multifunctionality, and sustainability image matter.

Figure 8: BIPV window louvere

Standards & Certification – The Regulatory Backbone

Since BIPV combines building-envelope function with photovoltaic generation, it must satisfy both construction-product regulations and PV module/system standards.

1. Key Standards and Guidelines

- IEC 63092 – “Photovoltaics in buildings – Building-integrated photovoltaic modules & systems.” This standard defines technical and safety requirements for BIPV modules when used as building products (e.g. mechanical strength, weather resistance, fire safety, electrical safety).

- Module-level PV standards (e.g. IEC 61215 for design qualification / type approval and IEC 61730 for safety) remain relevant for assessing PV performance and electrical safety. (Even if embedded, the PV cells still must meet PV-specific performance and safety criteria.)

- National / regional building / construction product regulations – many jurisdictions require that any building envelope material (cladding, façade, roofing, glazing) must meet building code provisions for wind loads, fire, watertightness, structural integrity, durability. When a PV module replaces conventional material, it must meet those too.

2. Importance of Standards Compliance

BIPV modules serve dual roles (building envelope + power source), failure or misuse can compromise building safety, weather protection, or fire safety – not just power output. Standards like IEC 63092 exist to manage these dual aspects.

In many countries, building authorities and code inspectors may require documentation/certification showing that the BIPV components meet both PV and building-product standards before granting building / occupancy permits.

Therefore, if you plan to use BIPV, you must plan early – involve architects, structural / fire code consultants, PV engineers, façade specialists and regulatory consultants from the very first design sketch. Trying to retrofit BIPV onto an existing envelope – or inserting PV after envelope design is final – often leads to failures or costly rework.

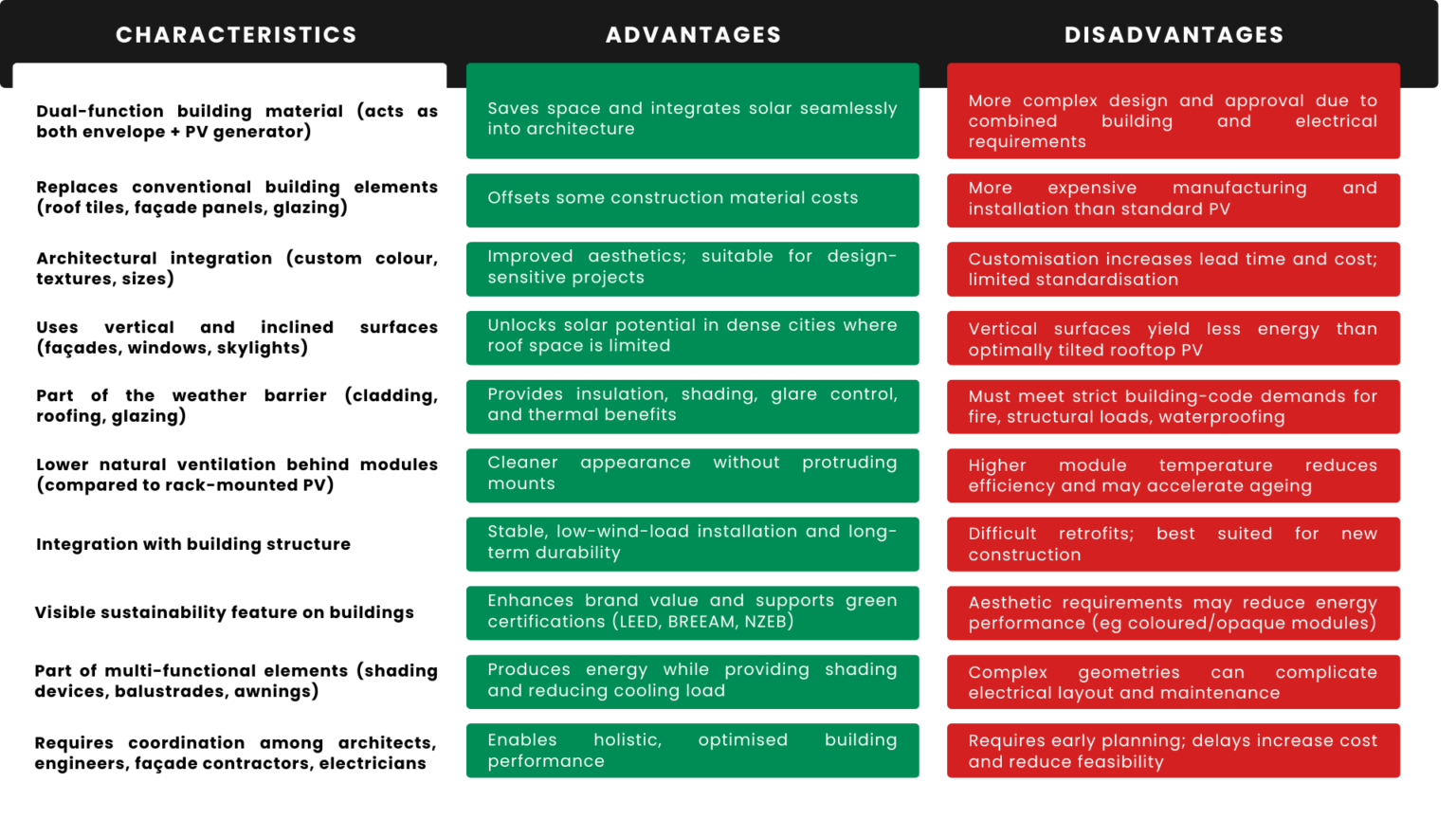

3. Advantages & Disadvantages of BIPV

Figure 9: Advantages and Disadvantages of BIPV

Conclusion

BIPV calls for a shift from “adding solar” to building with solar—treating PV as a core construction material, not an accessory. As standards like IEC 63092 expand and cities push for net-zero buildings, the envelope itself becomes a power asset. The real potential lies in designing façades and roofs that balance daylight, comfort, and energy generation as one integrated system. When viewed not as an added cost but as a replacement for traditional materials, BIPV becomes a smarter way to build in dense, climate-driven cities. It’s not a universal solution, but when applied with intention, it points toward a future where architecture doubles as clean-energy infrastructure.