Introduction

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is an intensive analytical approach used to evaluate the energy consumption and environmental implications of a product throughout all phases of its life cycle. In the context of solar photovoltaic (PV) technologies, conducting LCA studies is vital to identify and address environmental and energy-related concerns, hence aiding the sustainable progress of PV systems.

As the PV market expands, it is important to understand their evolution and evaluate their current and future energy and environmental performance.

This article establishes the methodology for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) adapted from the IS/IEC TS 62994: 2019.

LCA Framework

The internationally recognized standards ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 define the structure of LCA, which includes four primary phases:

- Goal and Scope Definition

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

- Interpretation

Figure 1: Stages of life cycle assessment (LCA)

Source: ISO 14040:2006

Foundational Principles of PV LCA

Normative Basis

The quantification and reporting of any LCA must be in accordance with the principles of the LCA methodology provided in ISO 14040 (Environmental management – Life cycle assessment – Principles and framework) and ISO 14044:2006 (Environmental management – Life cycle assessment – Requirements and guidelines). These fundamentals describe the basis for the subsequent requirements in the process.

Fundamentals

- Life Cycle Perspective: All stages- raw material acquisition, production, and the end-of-life stage- must be considered.

- Iterative Approach: The four LCA phases must be continuously reassessed.

- Scientific Approach: Decisions should primarily favour natural sciences (physics, chemistry, biology). Value choices are permitted only if no scientific basis exists, and their rationale must be clearly explained.

- Relevance: The chosen data and methods must be appropriate for assessing the emissions and resource consumptions of the PV system.

- Completeness: The study must include all unit processes, life cycle stages, emissions, and resource consumptions that significantly contribute to the environmental impacts.

- Consistency: Assumptions, methods, and data must be applied uniformly throughout the study.

- Coherence: Recognized methodologies and standards for PV electricity production should be selected to enhance comparability between LCA studies.

- Accuracy: LCA quantification must be accurate, verifiable, relevant, and not misleading. Bias and uncertainties must be minimized.

- Transparency: All assumptions, methodologies, and data sources must be openly and comprehensively documented.

- Focus on Routine Operation: The LCA quantifies impacts only from ordinary foreseen routine operations, not from accidental, non-routine events. (To read more on the Routine and Non- Routine Operations, refer to the previous article ‘Lifecycle of PV Modules: Environmental, Health & Safety Risk Assessment’.)

Phase I: Goal and Scope Definition

This section of the LCA process establishes the precise context, boundaries, and technical assumptions for the PV system analysis. It is critical for ensuring the principles of consistency, relevance, and completeness are met.

1. Defining the Goal of the Study

The process of conducting a Life Cycle Assessment begins with defining the goal, which constitutes the most fundamental step in establishing the study’s scope. The goal definition explicitly specifies the intended application of the results—whether the LCA is for reporting the environmental profile of a currently installed PV system, comparing technologies, informing a supplier choice, or modeling a large-scale future energy transition. This decision is critical because it directly dictates the choice of the Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) System Model (i.e., Attributional, Decisional, or Consequential). The goal also defines the intended audience (e.g., public, government, internal management), which governs the level of detail required in the final communication and ensures that the eventual conclusions and recommendations drawn in the Interpretation phase are in accordance with the study’s initial purpose.

2. Determine the Functional Unit and Reference Flows

Post establishing the goal, determine the unit of output that the study will use to compare the PV system’s environmental impact against other technologies.

i) Mandatory Functional Unit: The functional unit shall be electricity generated in kWh. This ensures comparisons are based on the final useful energy output, not just the installed capacity.

ii) Reference Flows (For Component Analysis Only):

- m2 module: Used for quantifying the impacts of the building or the supporting structures (excluding modules and inverters). It is not suited for comparisons of PV technologies due to efficiency differences.

- kWp (rated DC peak power under STC): Used for quantifying the impacts of electrical parts (inverter, transformer, wire). It is not suited for comparisons of module technologies, as the actual kWh fed to the grid may differ.

3. Establishing the System Boundary

The system boundary defines all processes included in and excluded from the study under the Life Cycle Perspective.

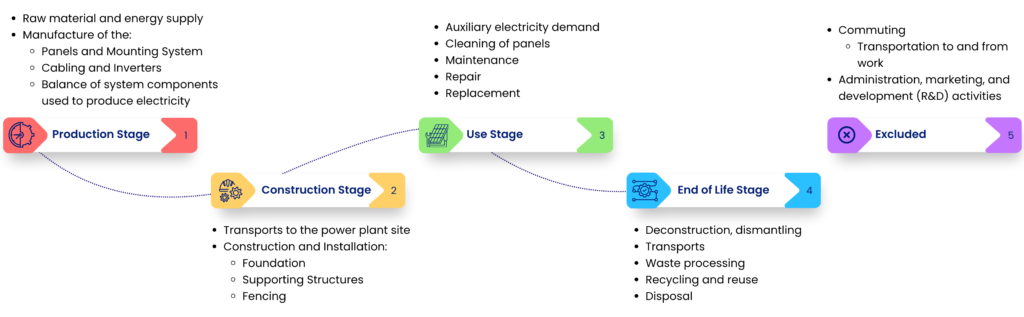

Figure 2: Life Cycle Phases of LCA

4. Setting PV-Specific Technical Parameters

This section is paramount because it converts the theoretical capacity of the PV system (measured in kWp or m2) into the actual functional unit of the study: kWh electricity delivered over the lifetime. Without these specific PV assumptions, the LCI (data collection) phase would be based on inaccurate system performance, violating the principle of Accuracy.

The parameters must be set as follows:

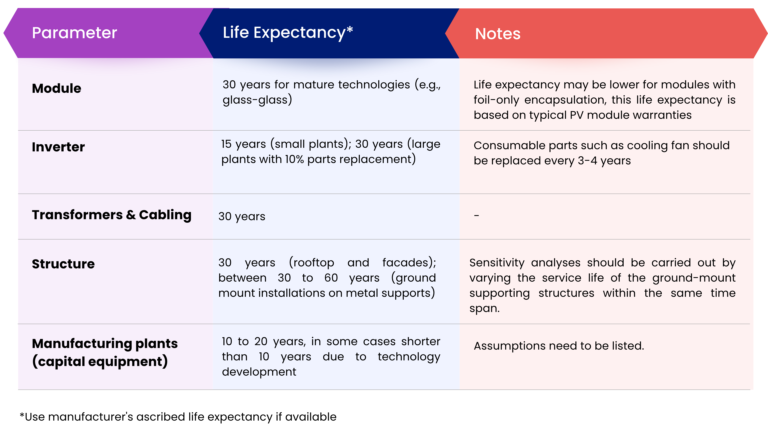

i) Life Expectancy

The lifespan defines the study period, directly influencing the total kWh output and the frequency of replacement parts accounted for in the inventory.

Figure 3: Life Expectancy of the PV Components

ii) Irradiation

Irradiation is the fundamental input driving electricity generation. The method used to model the solar resource must be clearly specified.

- The total irradiation used in the calculation should be representative of the system’s location, orientation, and tilt to maintain relevance to the specific study goal.

- The actual method for modelling irradiation (e.g., assuming optimal orientation, or using average values for typically installed systems) shall be specified in the final report.

iii) Performance Ratio

The PR accounts for all real-world system losses (e.g., dirt, wiring, temperature) between the DC power produced by the module and the AC power delivered to the grid.

- The PR is the essential link between the theoretical performance kWh and the actual environmental burden.

- Default Values: If system-specific data is unavailable, use the following defaults:

- Roof-top PV: Default PR of 0.75.

- Ground-mounted utility installations: Default PR of 0.80.

iv) Degradation

Degradation accounts for the natural, progressive loss of efficiency over the long life of the module, ensuring the accuracy of the total kWh output calculated.

- Mature module technologies must assume a linear degradation profile. The degradation is assumed to decline to 80% of the initial efficiency over the 30-year lifetime, which translates to a linear rate of 0.7%/year unless actual data exist, in which case documentation has to be provided. When extrapolated from is the- specific data, it should be clearly stated with

- For sensitivity analysis, consider 0.5%/year degradation rate until the end of life (30 years).

- The degradation curve must start from the lower value of the nameplate capacity printed on the data sheet, not the average or maximum tested value.

Phase II: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) phase is the data collection and modelling core of the LCA, quantifying all inputs (resources, energy) and outputs (emissions, waste) for the system defined in Phase I. This phase relies on consistency and completeness.

1. Data Collection and Process Definition

This initial step establishes the methodological approach to collecting data based on the study’s scope and goal.

i) Defining System Models

To maintain Consistency, the environmental burden of background processes (especially the electricity used) must be modeled based on the study’s goal (chosen in Phase I):

Figure 4: System Model Approaches for LCA

ii) Universal Recommendations

The goal and scope can vary by product system however some recommendations remain universally applicable.

- The Process Split: The entire PV product system is divided to manage data collection:

- Foreground Processes: These are the processes that the decision-maker or product-owner can influence directly. This typically includes the final module manufacturing steps, site installation, and the operational activities (cleaning, maintenance).

- Background Processes: These are all remaining processes of the particular product system. This covers indirect, upstream activities, such as the initial energy required for polysilicon refinement, steel production for mounting structures, or global transportation logistics.

- Use conventional process based LCA and follow ISO standards.

- Avoid Input–Output-based LCA for PV systems, as it lacks process-specific precision.

- If a hybrid approach is chosen, report transparently and provide justification for using it.

2. Allocation and Recycling

Allocation is required to solve the problem of multi-functionality, ensuring that the environmental burden of a process is shared accurately among all its co-products or is tracked correctly across multiple life cycles (recycling).

i) General Allocation Rule

Consistent allocation rules must be applied for all multi-function processes throughout the inventory analysis.

ii) Recycling Allocation (The Cut-off Rule)

For material recycling, the methodology must be clearly defined:

- Recommended Default: The primary method should be cut-off allocation. The recycled material entering the PV system life cycle is considered to have zero burden (its past environmental history is “cut off”).

- Sensitivity Analysis: The end-of-life (avoided burden) approach (where the PV system is credited for the downstream recycling) may be used, but only for sensitivity analysis to test the robustness of the results.

3. Final Inventory Compilation

The final output of Phase II is the Life Cycle Inventory (LCI), a comprehensive table that lists every input (e.g., kg of water, MJ of oil) and output (e.g., kg of CO2, kg of waste) associated with the PV module system, all normalized to the functional unit (kWh of AC electricity delivered).

Phase III: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

This phase is where the raw data collected in the Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) is translated into quantified environmental impacts. The goal is to produce an LCIA profile for the PV system, ensuring the result is verifiable and accurate.

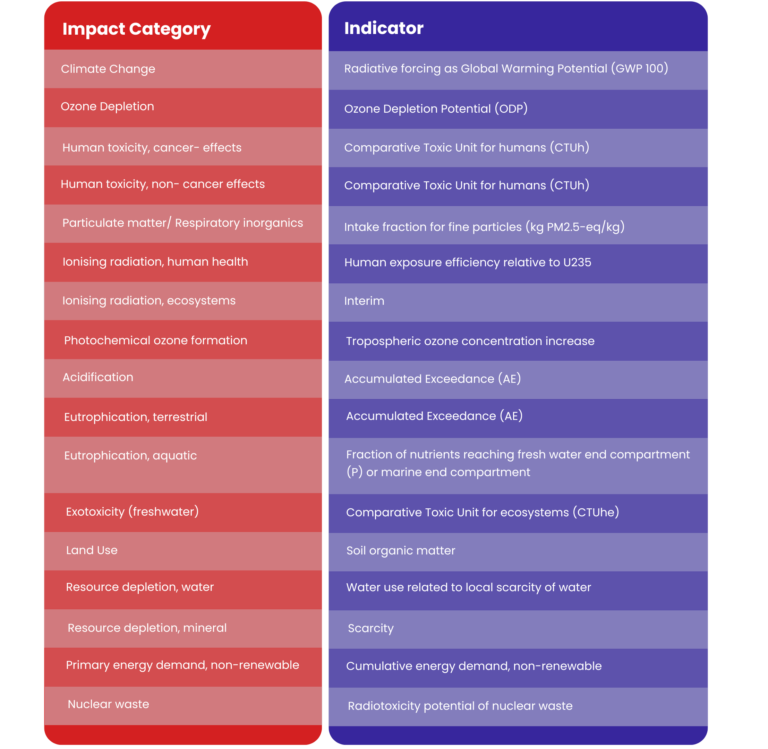

The LCIA begins by processing the inventory data into meaningful environmental categories.

1. Classification

- Action: Group all the elementary flows (inputs and outputs) from the LCI into specific environmental impact categories (e.g., global warming, ozone depletion, human toxicity, resource depletion, etc.).

- Purpose: To sort emissions and resource extractions by the type of environmental problem they contribute to.

2. Characterization

- Action: Convert the classified LCI data into common equivalent units for each impact category using characterization factors (e.g., Global Warming Potentials).

- Purpose: To produce a single numerical indicator for each impact category. For example, emissions of methane and nitrous oxide are converted and summed up as kilograms of CO2 equivalents kg CO2 -eq.

- Outcome: The LCIA Profile—a list showing the magnitude of potential impacts (e.g., X kg CO2-eq per kWh)

Figure 5: Impact Categories and Indicators

Source: IS/IEC TS 62994:2019

Phase IV: Interpretation

Interpretation is the final mandatory phase of the LCA procedure, in which the results of an LCI (Life Cycle Inventory Analysis) or an LCIA (Life Cycle Impact Assessment), or both, are summarised and discussed as a basis for conclusions, recommendations, and decision-making in accordance with the definition of the goal and scope of the LCA.

Some of the impact indicators described below and calculated in the impact assessment phase may further be processed into payback times or into energy return on investment.

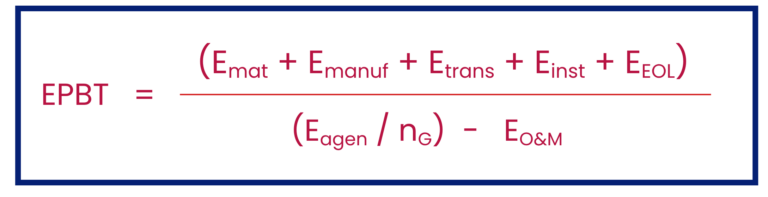

1. Energy Payback Time (EPBT) or Non- Renewable Energy Payback Time (NREPBT)

The EPBT is a crucial reporting requirement that quantifies the time needed for the PV system to generate the same amount of primary energy that was consumed to produce it.

Where:

- Emat, Emanuf, Etrans, Einst, EEOL: The total Primary Energy Demand for materials, manufacturing, transport, installation, and end-of-life, respectively.

- Eagen: Annual electricity generation kWh.

- nG: Grid efficiency (the average primary energy to electricity conversion efficiency).

- EO&M: Annual primary energy demand for operation and maintenance.

Reasoning and assumptions applied to identify the relevant grid mix shall be documented.

Based on the above definition, two approaches exist to calculate the EPBT of PV Power Systems.

i) PV as a replacement of the set of energy resources used in the power grid mix.

ii) PV as a replacement of the non-renewable energy resources used in the power grid mix.

2. Environmental Impact Mitigation Potentials

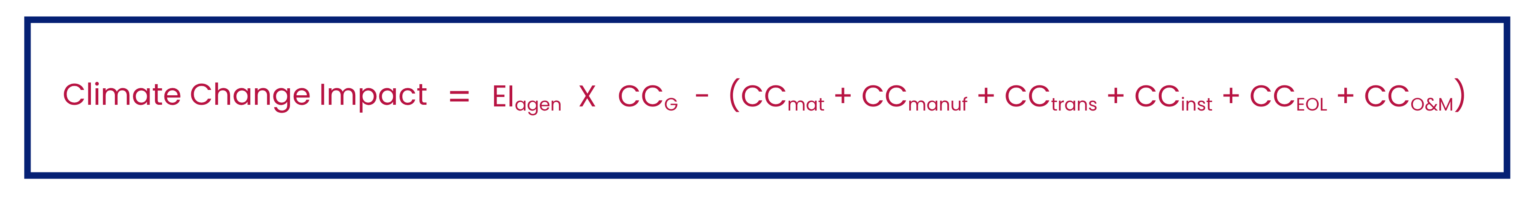

This metric quantifies the environmental benefit achieved by using PV electricity instead of the baseline (e.g., the grid mix). The Climate Change Impact Mitigation Potential is calculated as the difference between the impact avoided by displacing grid power and the impact caused by producing the PV system.

Where:

- EIagen: The life cycle electricity generation kWh.

- CCG: The climate change impact (in kg CO2-eq kWh) of the grid electricity that the PV system displaces.

- CCmat, CCmanuf, CCtrans, CCinst, CCEOL, CCO&M: The climate change impacts (in kg CO2-eq) of the PV system’s life cycle phases.

Reporting and Communication

The final output is the report, which serves as the permanent record of the LCA. It must be prepared to ensure the conclusions are not misleading and fully transparent.

The final report shall document all essential parameters, assumptions and results, some of which are:

1.Module-level LCAs should summarize:

i) PV technology

ii) Type of system

iii) Module related parameters

iv) Irradiation

v) Location, etc.

2. The report should also specify:

i) Goal and scope

ii) System boundaries

iii) Functional unit

iv) Any allocation or recycling assumptions relevant to the module’s life cycle

Conclusion

The Life Cycle Assessment of PV modules offer a thorough methodology for assessing their energy and environmental performance throughout the course of their lifetime. Through the integration of globally accepted standards like ISO 14040/14044 and PV-specific guidelines from IEC TS 62994:2019, life cycle assessment (LCA) assists in identifying important stages where modifications can lower emissions and improve energy efficiency. A comprehensive understanding of PV sustainability is ensured by using statistics like as EPBT, EROI, and environmental impact categories. In the end, these evaluations are essential for improving PV module design, directing material selection, and attaining a future that is cleaner and more energy efficient.